Breaking Barriers: Scaling Up the Hydrogen Supply Chain

Published on August 02, 2023

13 minutes

Article available in Chinese, Japanese and Korean:

-

Chinese (Traditional)

Download the document PDF (1.18 MB) -

Chinese (Simplified)

Download the document PDF (1.17 MB) -

Japanese

Download the document PDF (1.18 MB) -

Korean

Download the document PDF (1.25 MB)

With its potential to revolutionise industries for a cleaner future, hydrogen is irrefutably a pivotal piece in the energy transition puzzle. The immense potential of hydrogen remains a vision until it is fully unlocked, and to do so, industries have to navigate the complex landscape of the hydrogen supply chain, to seamlessly connect its producers and end users.

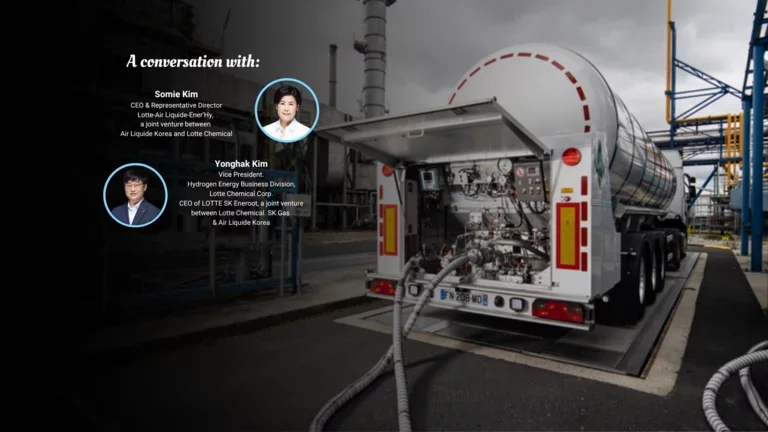

We invite Somie Kim from Lotte-Air Liquide Ener’Hy and Yonghak Kim from Lotte Chemical Corporation (LCC), to share what they think are the key steps to breaking the barriers of hydrogen today, so that it can be effectively scaled up for widespread adoption.

Where does the Asia-Pacific region stand in terms of hydrogen capabilities, in the global race for energy transition?

It is indeed a global race and given the diversity of geographies and needs in the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region, countries are running at different speeds. When it comes to hydrogen, “capability” can be seen as having the infrastructure to support the production or procurement of hydrogen molecules, to conditioning, transporting, storing, and distributing hydrogen in the form that is most appropriate for its end use. Such know-how has been in the trade for years, but doing so while emitting little to no carbon emissions is a challenge. Depending on the source and the use case of hydrogen, a tailored set of solutions is required.

In parts of Asia that are less endowed with renewable sources, countries are actively looking into importing low carbon hydrogen from the Pacific or Middle East. South Korea plans to establish low carbon hydrogen production facilities abroad and import those molecules in a form of ammonia or liquid hydrogen for domestic use. With this, Air Liquide Korea (ALK) and LCC have recently signed a memorandum of understanding to combine their expertise in ammonia cracking and liquid hydrogen conditioning and distribution in the Yeosu area. Japan has built and sent the world’s first liquid hydrogen carrier ship, The Suiso Frontier, on a voyage to and fro Australia, as a pilot prior to increasing hydrogen import at commercial scale. The ship carrying liquid hydrogen back to Japan demonstrates the technical capability of an international hydrogen supply chain. On the other hand, China, with abundant renewable resources, is looking to connect its renewable energy power plants in the northwest to electricity demand in the southeast to be able to convert large volumes of fossil-based hydrogen to clean hydrogen. Hence, I don’t believe that APAC is lagging behind countries in other regions.

I agree with Somie. In addition, South Korea is one of the most developed and ambitious countries at the forefront of hydrogen technologies and adoption. Its use cases are currently centred on mobility, and soon power generation. In fact, Hyundai Motors was a global first-mover in hydrogen fuel cell technology by mass producing the world's first Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle (FCEV) which is now being used not just in Korea, but also Europe and as far as the United States.

Additionally, LCC, POSCO, Samsung Engineering and National Oil Corporation are cooperating with Sarawak Economic Development Corporation for a 1.1 GW of Green Ammonia project in Sarawak, Malaysia. Also, Lotte Fine Chemical and Aramco have signed a Memorandum of Understanding in January 2022 for low-carbon ammonia, and signed a subsequent supply agreement in October 2022 for the import of 50,000 tons of ammonia (25,000 tons of Sabic, 25,000 tons of Ma’aden). This is part of LCC’s 2030 roadmap of ‘Every Step for H2’ roadmap, to invest 6 tKRW for 1.2 mTon of clean hydrogen production and sales, inclusive of clean ammonia import.

I think we can both agree that hydrogen is imminent for the energy transition and most countries in APAC are already taking steps towards improving the hydrogen ecosystem infrastructure and gradually moving to a low carbon supply chain.

Is industry at the mercy of governments when it comes to hydrogen?

The support of governments can certainly accelerate the Hydrogen industry. However, industry is not necessarily at the mercy of governments, because there are many industry frontrunners to prove that! I believe that collaborative efforts within the industry would be more critical, as we can leverage each other’s expertise and work together to achieve something greater. For example, HysetCo is a hydrogen mobility start-up by four companies, including Air Liquide, who have a common interest in promoting decarbonised road mobility. By joining hands, HysetCo is able to capture the demand, facilitate the funding of hydrogen infrastructure, and accelerate cost reduction by attaining economies of scale. Through the joint investment, HysetCo has deployed hydrogen refuelling stations and distributed 100 tonnes of hydrogen in 2022, the equivalent of 40,000 refuellings.

Similarly, ALK has joined forces with LCC in two separate strategic alliances to foster the rise of the hydrogen economy. Lotte-Air Liquide Ener’Hy being one of them, has an initial focus on building a sustainable and competitive hydrogen supply chain for mobility markets in South Korea. The first project is a large-scale high-pressure hydrogen filling centre, which utilises by-product hydrogen from LCC, on the site of the company’s Daesan plant. The centre will have an annual capacity of more than 5,500 tons, which is enough to charge 4,300 cars or 750 commercial buses per day. By collaborating to invest in hydrogen infrastructure, we are able to position ourselves for a clean mobility future.

ALK is also the only industrial gas company to participate in two national consortiums for the deployment of hydrogen refuelling infrastructure, HyNET and KOHYGEN. Government financial support made it possible to quickly scale up the number of hydrogen refuelling stations and vehicles. In turn, Air Liquide has been able to supply 19 refuelling stations nationwide and hydrogen molecules to 6 refuelling stations in South Korea, which serve the Seoul Metropolitan Area as well as local communities in the west and south.

Yes, Lotte-Air-Liquide Ener’Hy, is a prime example that industry can also lead the way. However, when it comes to the establishment of the hydrogen ecosystem in its early stages, the role of the government is crucial too.

We expect that the ecosystem of the hydrogen industry will be formed progressively, from power generation to mobility (including ship, aircraft and train) to the general industries (steel, petrochemical, cement, electronics, etc). Currently, the ecosystem formation is in the early stages across all areas, hence technological development, ease of application, and presence of strong demand sources are factors that will determine the speed of activation. The government is hence the most reliable economic entity that can contribute to the establishment of the ecosystem in its early stage, through clear directions and related support.

In Korea, power generation is a field the government can develop easily. In other fields where strong and unified demands are lacking, I believe it will require some time before the ecosystem is activated regardless of government support. The problem arises when the required time span is extended, as it creates a possibility that prevents the complete cycle of hydrogen economy activation. It implies that the role of the government, which can exercise influence in the power generation field, is very important. This is because the establishment of the hydrogen ecosystem in the power generation field earlier on can serve as priming water to shorten the period of hydrogen ecosystem formation in other fields through the establishment of the economies of scale.

Is it possible to scale up the adoption of liquid hydrogen?

The question is about supply chain, the technological development, establishment of a distribution network, and demand. It will be challenging to effectively establish a hydrogen ecosystem if an issue arises in any of the aforementioned factors. Considering that the hydrogen ecosystem is still in its early stage of establishment, I think demand is the most important factor.

Hydrogen is a chemical substance with the highest volatility. So, whether it is in the gaseous or liquid state, the transportation and storage of hydrogen is extremely costly. To this end, for any hydrogen project, the demand can be secured earlier on, after there is a plan to improve economic feasibility, by minimising the storage and transportation cost. Therefore, I believe the top priority is to develop a business model that produces hydrogen near large-scale demand and supply it through a pipeline to create economies of scale. For users with small-scale demand, it is not feasible to supply hydrogen through a pipeline. As a result, hydrogen transportation and storage are inevitably required.

Therefore, a decision for gaseous or liquified hydrogen is necessary. In this case, the decision must be made by comprehensively considering the logistics and energy cost. The key point, I think, would be the expected demand for hydrogen volume. In Korea, we believe that the demand for liquefied hydrogen with economic feasibility will be created around 2027 to 2030.

We are fully aligned. Demand creation is in fact one of the strategies of the South Korean government’s Clean Hydrogen Ecosystem Creation Plan, which by 2030, targets the deployment of 30,000 commercial hydrogen vehicles and supports the consequent hydrogen demand with 70 liquid hydrogen refuelling stations.

The use of liquid hydrogen is of increasing importance in mobility and ALK is ready to step up with its proven track record in liquid hydrogen conditioning and distribution. Air Liquide Engineering & Construction supplied the first hydrogen liquifier of 5 ton/day in Changwon, and another 90 ton/day unit is under construction to be supplied in Incheon - the largest capacity yet in Korea. In Europe, commercial activities surrounding liquid hydrogen for carbon-free aviation have already started through the creation of the Hydrogen Airport, a venture between Air Liquide and Groupe ADP.

What is the potential of a sustainable hydrogen supply?

The potential is significant and holds promise in various sectors. Hydrogen is an abundant element that can be produced from a variety of sources, including renewable energy, water electrolysis, and biomass. When produced using renewable sources, Hydrogen is considered “green” and offers several advantages.

To support energy transition, new applications for hydrogen are being developed for carbon-intensive industries and in mobility - road, maritime, and aviation included. Given the multiple use cases of hydrogen, being able to produce it cleanly would mean greatly reducing the carbon footprint of all these processes.

The launch of new generation hydrogen vehicles from Hyundai, Toyota, Honda, and other car manufacturers have placed the spotlight on transport operators to convert their fleet to an emission-free one by utilising FCEV. Fleet by fleet, road emissions can be greatly reduced. Concurrently, there are maritime and aviation studies worldwide looking at scaling up onboard hydrogen fuel tanks, which could revolutionise the way we travel.

Having a stable, reliable and sustainable hydrogen supply also allows us to store it, either as a gas or liquid, to compensate for the intermittency of renewable energy. With the versatility of hydrogen as an energy carrier, coupled with Air Liquide’s expertise in hydrogen conditioning and distribution, we can transform how we power businesses and homes in the future.

The potential is undisputed, especially since hydrogen is now seen as critical to curb greenhouse gas emissions. However, it is all the more difficult to secure economic feasibility as the production cost increases due to the renewable energy use or carbon capture and storage. The three key factors to secure a sustainable hydrogen supply are the establishment of economies of scale, infrastructure, and technological development - and to unlock the potential of a sustainable hydrogen supply, I believe it is imperative for us to focus on achieving these factors.

What tangible actions is the Lotte-Air Liquide Ener’Hy venture taking to act on establishing a sustainable hydrogen economy?

The three rules of thumb for successful operation of Ener’Hy, are growth, sustainability, and harmony. If collaboration stops at Daesan hydrogen filling centre, without growing our partnership further, the joint venture will achieve limited success. Therefore, we also aim to start collaborative efforts in Ulsan and Yeosu in the near future to sustain the success of our joint ventureWe also need to create business in various areas as standalone businesses, as the one to only sell hydrogen to hydrogen charging stations, is extremely vulnerable in times of a crisis. So, for the highly purified hydrogen, we are planning to review a plan for hydrogen sale regardless of its distribution to hydrogen charging stations. In the short-term, we are also reviewing a hydrogen purification business, which will contribute to sustainable operation of the joint venture. Lastly, I find harmony between two companies in a joint venture extremely crucial. A lack of synergy between companies will disrupt successful business implementation, and it is highly likely that time and resources will be consumed in the course of dissension. Therefore, we will continue to dedicate strong effort to develop the Lotte-Air Liquide Ener’Hy joint venture as one that is based on mutual trust.

Hydrogen produced today is largely fossil-based. What would be the tipping point to push industries to produce hydrogen with renewable sources?

That is the case because large-scale renewable energy capabilities are still being built up today and some regions do not have adequate resources to do so. Still, many countries have made international commitments towards carbon neutrality and it is a matter of time before countries start producing or importing hydrogen with renewable sources.

In this aspect, APAC has much to learn from Europe, who pioneered the offering of state funding for the development of commercial-scale electrolysers to produce renewable hydrogen. Normand’Hy was supported by the French government to be one of the first-movers in sustainable hydrogen supply, allowing Air Liquide to build its ambition to be a major supporter of the decarbonisation of industry and mobility markets. Adequate subsidies will allow renewable hydrogen projects like Normand’Hy to overcome the chicken-and-egg problem in the hydrogen economy, by offering a competitive supply of renewable hydrogen.

Additionally, the transition of polluting sectors such as power generation and transportation will require a regulatory nudge, best accompanied with incentives, to phase out fossil-based means.

What ecosystem is necessary for a hydrogen economy to take flight?

About 40 years ago, in Korea, there was a concern in establishing the liquified natural gas (LNG) ecosystem, which is similar to the establishment of the current hydrogen ecosystem. Back then, the Korean government led the development of nationwide infrastructure (import terminals, auxiliary facilities, piping systems, etc) to ensure economic feasibility, and succeeded in replacing existing energy sources at a very rapid pace. I believe that the hydrogen ecosystem must go through a similar process. This time, it will be led by industry who are at the forefront of hydrogen technologies and solutions. However, if the government plays a public interest role in certifying clean hydrogen and providing initial incentives (especially in the field of power generation), it will truly be a game-changer and the time taken to establish a hydrogen ecosystem will be accelerated.

I agree, and it will definitely require many players coming together. We need to be able to capture and consolidate the demand for hydrogen. Industrial gas companies must refine hydrogen supply chain technology and equipment manufacturers should focus on mass production of reliable and durable hydrogen technologies. Governments around the world can provide incentives for hydrogen ecosystem participants, while also discouraging traditional, fossil-based solutions. Most importantly, to bring stability to the hydrogen economy, authority intervention is necessary to regulate any price volatility of hydrogen in the long term. All players must step up to the challenge - it takes a village to make a difference!